When it comes to the recovery landscape in Arkansas, Kyle Brewer, BS, PR, NCPRSS has been at the center of innovation – both as a professional and as someone with lived experience of substance use disorder. Starting off his career as one of the first Peer Recovery Specialists in the state of Arkansas after graduating from the University of Central Arkansas, he brought his expertise to patients who entered the University of Arkansas Medical Sciences emergency department. By offering patients resources on the spot via a friendly face who could relate to them on a level of shared understanding, Brewer quickly found success in the hospital and scaled his work to other departments, then other hospitals throughout the state.

His efforts were noticed by various addiction and recovery organizations, one being NAADAC (National Association of Addiction Professionals) where he joined to streamline and formalize the peer support and recovery process. As his career evolved from UAMS to NAADAC, then the Arkansas Supreme Court soon after, he would eventually pivot to his current position: the Clinical Liaison of Landmark Recovery.

As Brewer puts it, all of the aspects of his past role that he loves are wrapped up in his work at Landmark Recovery, a national drug and alcohol treatment center network with a location just outside of Little Rock in Morrilton, Arkansas. Through formalized business development and the purpose-driven work of connecting people struggling with substance use disorder to treatment, his lifelong mission to serve others is fully manifested.

We’re thrilled to share a candid conversation with Brewer about his backstory of grappling with addiction, the evolution of his career, and his vision for recovery in Arkansas.

End Overdose: Can you tell us about your background in Arkansas and what inspired you to pursue your bachelor's in addiction studies?

Kyle Brewer: I abused alcohol and drugs as a teenager. As an adolescent, I got in trouble a few times [and was put on] probation. Went to treatment. But I maintained my academics. And that was always something that was going in my favor. I always showed up and went to school. But after I went to treatment when I was 17, I came back, I started hanging out with a different group of friends and I went off to college to UCA. I learned that I'm a registered Native American, I’m a quarter Oneida, so I had the ability to receive a scholarship for college. I went to UCA and my freshman year I had my wisdom teeth removed, so they prescribed me an opiate for the pain. From that point onward, I started abusing pain pills pretty bad. When figuring out my major, I started in the psychology department because I've always enjoyed talking to people. I think the brain is a fascinating thing. Every individual and the way they process and think is very unique. Like a snowflake, it's so complex. It's just a really beautiful thing.

So I've always found psychology and human beings to be interesting. I was always that person at the party in deep conversation with a group talking about life. And so I've always liked just engaging and having conversations with people and getting deep. That's what got me interested in the psychology department. I was going throughout college, doing my thing. I joined a fraternity. And you get a big bro, like a mentor, someone already in the fraternity. When I was talking to him, he told me he was in the addiction studies program and I didn't even know it existed. That’s a really broad major that you've really gotta go on and get a master's and even a doctorate in if you really want to do something with it. And so I've had a lot of substance use and incarceration, things like that surrounding addiction. Most everybody besides my mom and my little sister has had their own battle with addiction. Family members in and out of the penitentiary, all my childhood and adolescent years, visiting them. So I thought, going into the addiction studies program, my initial motivation was that this is my way of helping others. I've seen how this can impact people and their families and so I wanna help other people.

And then just to be frank with you, drugs were interesting to me. Not only did I enjoy doing them, but I enjoyed learning about them. So that's really what got me focused on the addiction stage program versus general psychology.

This whole story makes sense today. Everything I do lines up with my degree, but as it was unfolding, it didn't make any sense, honestly. In my personal life, I was abusing prescription opiates daily. That just got worse throughout college. Somewhere along the way, as with opiate addiction, it stopped being about the high and it started being about, I have to take this or I get sick, or I'm gonna go into withdrawal. Trying to do everything I can to not go into withdrawal.

Around my senior year when I was spending thousands of dollars and burning through scholarship money within a couple months, my family started realizing that something was going on, and so my mom just thought that if she enabled me and got me to graduation day, that I would get a degree, I would get a job, I would grow up, and I'd put all that behind me.

So that’s what allowed her in her mind to enable me. I graduated, and there's a picture that I always show that I'm doing presentations and it's my graduation day and, I'm smiling, I have my family around me. I'm the first in my family to graduate from a four year university, so it looks like, on the surface it would be a really exciting, joyful day, and you would probably scroll through social media like the posts and say congratulations.

That's what it looked like on the surface, but, what was going on underneath that? The other story was how I'd woken up that morning and because we're partying for graduation, I'd used all my pills and I was in panic mode, anxious, and my hands were starting to sweat and my stomach was starting to be upset.

I knew I had to find something so I could feel well, and not be sick all day and participate in my graduation. I remember frantically scrolling through my phone and finally finding seven hydrocodone, 7.5 milligrams, chewed those up, by no means was that getting me high anymore. That just kept the withdrawal symptoms at bay for me to pick up my degree and participate in activities. The inspiration behind the addiction studies was initially because of all the stuff that I'd seen it put my family through, then I had my own personal interest in drugs, counseling, talking to people and trying to help others.

EO: That's super interesting. I got sober my senior year of college, and there’s pictures of me in my early senior year where I looked as happy as can be, when in reality, I was like bottoming out in addiction. It's bizarre, the image we project versus what's happening internally.

KB: Yes, the surface does not tell the story a lot of the times, and especially when it comes to addiction. You could be in a multimillion dollar house, in a very successful career and have a family, and all the things, but still be in the middle of a substance use disorder. Just because your life isn't in shambles and you’re not homeless or in jail, that doesn't mean you don't have an issue with substances. I like to talk about stigma. We have this idea from just media or movies or just, growing up, just having these kinds of skewed perceptions about different issues in our society. I feel like we often don't associate success and doing well, and smiling and happiness, with someone in active addiction.

EO: Absolutely. I would love to hear about your early professional days, working as a peer recovery specialist, how that process evolved.

KB: In 2017, after I graduated college in 2013, all the things happened. I'd moved on from pills to heroin to snorting to shooting up all the things, destroying everything. I found myself in a homeless shelter in Little Rock in 2017. I went to a hospital and was faced with a decision on what I needed to do when I left there, because I didn't have anywhere to go. No options. So I went back to that homeless shelter, entered into their nine month, faith-based, recovery program. I stayed there for a year. That's where I got my foundation for recovery, for faith, for the lifestyle that I live today.

After being there for a year, I started working at a church. The peer support and recovery support program, and just the peer specialist position in general, was brand new to Arkansas on the substance use side; it was just getting started.

I had someone approach me at an event where I spoke at our church. I shared my story and they asked if I wanted to go through peer support training. I was happy with what I was doing. I just looked at it as maybe an opportunity to have more resources and tools to help more people.

I went through the training, not knowing that three months later, there would be a job opportunity at UAMS in the emergency department. A friend of mine sent it to me and said, man, this looks like something that's right up your alley that you would enjoy doing. So I applied. I got that job. So I was the first person in the state of Arkansas to be stationed as a peer support specialist in an emergency department hospital setting. There was no playbook, nobody had done it in the state. But I did have an attending physician, Dr. Mike Wilson, who wrote the grant and got the funding for the position. He was my direct supervisor, believed in mental health and addiction recovery, and the possibility in that and being a little innovative and thinking outside the box. And he also didn't micromanage me, so he allowed me to figure out what this looks like and how to do it best.

Over that first year, we worked with a little over 500 people that I came in contact with through the emergency department. So someone would come in for an overdose or drug and alcohol withdrawal or psychiatric issues. If there was substance use involved in it, I would be watching the track board in the emergency department. I would approach the room, knock, introduce myself as a peer support specialist, say I'm a person with lived experience, and have a conversation. If they're willing to talk, just talk through what was going on, relate to their story, and if they were willing or interested in doing something, we would complete a plan and get them accepted into treatment. We would set them up with resources, create the plan, and they went directly to the treatment facility or a support group and left with my cell phone number.

Three months into that, the social work and case management department found out about me. They enjoyed working with me, and it integrated throughout the entire hospital.

UAMS is a large hospital, a level one trauma center in Little Rock, and a university teaching hospital. It’s a very large organization, so I would not only work in the emergency department, but I would be like an extension of the psychiatry consult team. While on the medical floor, I spent a lot of time on the behavioral health unit, the psychiatric research institute. If there was substance use involved and someone was interested in recovery, they would call me. I would visit with people in the emergency department, but I'd also go visit with people while they were admitted in the hospital and help create plans or just encourage them. Build a relationship that was mainly trying to implement a new program in a large hospital system with different disciplines for attending physician, residents, social workers, patient care techs, nurses, and just navigating that in a way where it was collaborative, it was supportive of the patient, but they had no experience with a peer support specialist. It was the first time in the state. So being mindful that the experience I leave these professionals with is gonna have an impact on how they view this particular role.

Wherever they go in their next job, I want them to have had a good experience and believe in this role and the power of this position being part of the team. Mostly just direct services, connecting people to treatment, providing one-on-one support, following up with them once back in the community. That was the first year – I was one of the first peer support specialists in the state, and that was my main focus providing direct services to people.

Due to the amazing team at the hospital, it was very successful. We worked with over 500 people within the first year connected, 150 directly to treatment, and we were distributing nasal spray naloxone through this program. They would get a box of two doses of nasal spray whenever they left the hospital, so they didn't have to go to the pharmacy – we gave it to them there. I would also give them training on Narcan and how to use it. So we distributed a lot of naloxone over that first year.

But other hospitals across the state were becoming interested in this. And the state that was funding DHS, that was funding the position was interested in implementing in other hospitals. So then it went from providing direct services to consulting with other hospitals to help them implement this position system of care, whether in the emergency department or an inpatient behavioral health unit. I started helping people build and implement peer support programs. Then NAADAC came into the picture.

It was after about a year and a half working for UAMS, where we had worked on this three tier credentialing model for peer support specialists. There was the core level, advanced level, and peer supervisor. The idea is a peer specialist needs a peer supervisor, not necessarily a clinical supervisor who’s never worked in this role. There are distinct differences between clinical and nonclinical roles. They don't have lived experience, and don't necessarily understand it. Peers need peer supervisors. We created a career ladder for individuals to pursue three levels of credentials.

And so they, the state, decided to partner with NAADAC – The National Certification Commission for Addiction Professionals – to build out that program and implement it across the state, put structure, organization, and legitimacy behind it. Before NAADAC, it was just a training model.

There were these trainings that were offered and there were criteria that you had to meet, but no certification or credential and no back-up, no credibility behind it at that point. When they partnered with NAADAC, they wanted NAADAC to hire an in-state person that had been through it. Because I had been through all three levels, I was one of the first 10 peer supervisors in the state of Arkansas. They wanted someone that had been through the whole model that the DHS knew that they worked with and trusted.

NAADAC hired me and I met with their executive director a couple of times, and her name's Cynthia Moreno Tuohy, who was the executive director of NAADAC at the time, and really hit it off with her. I took that job and UAMS wanted me to stay. They knew I couldn't pass on the opportunity, so I stayed on with them part-time just so they had the ability to continue giving out my phone number, and in certain cases have me come talk to people, and just to continue to have me as a resource.

I stayed on with them part-time, but switched to NAADAC as my full-time job, and that was to take that training program that they had built in Arkansas and develop it into a really organized, streamlined, and structured legitimate certification and credentialing program that included testing, the whole application process, and membership process for NAADAC. It included building out and writing codes of ethics and creating an ethics review committee for the state. And so that, again, took me into this more of a leadership role, and building a statewide program for the peers themselves. So it went from working with individuals and providing services to people that are needing support in providing that type of support, and working with the workforce, and investing in the people providing the services. The NAADAC job took me from Arkansas. But then that naturally also put me onto the national scene and what was going on nationally.

We were looking at this three-tiered model as something we could implement on a national level to provide a career ladder and workforce opportunities for peer specialists that get tired of working an entry level peer support job for $15, $16 an hour and they decide they're gonna go back to school because they need to get a licensure or they need to get some credentials so they can make more money.

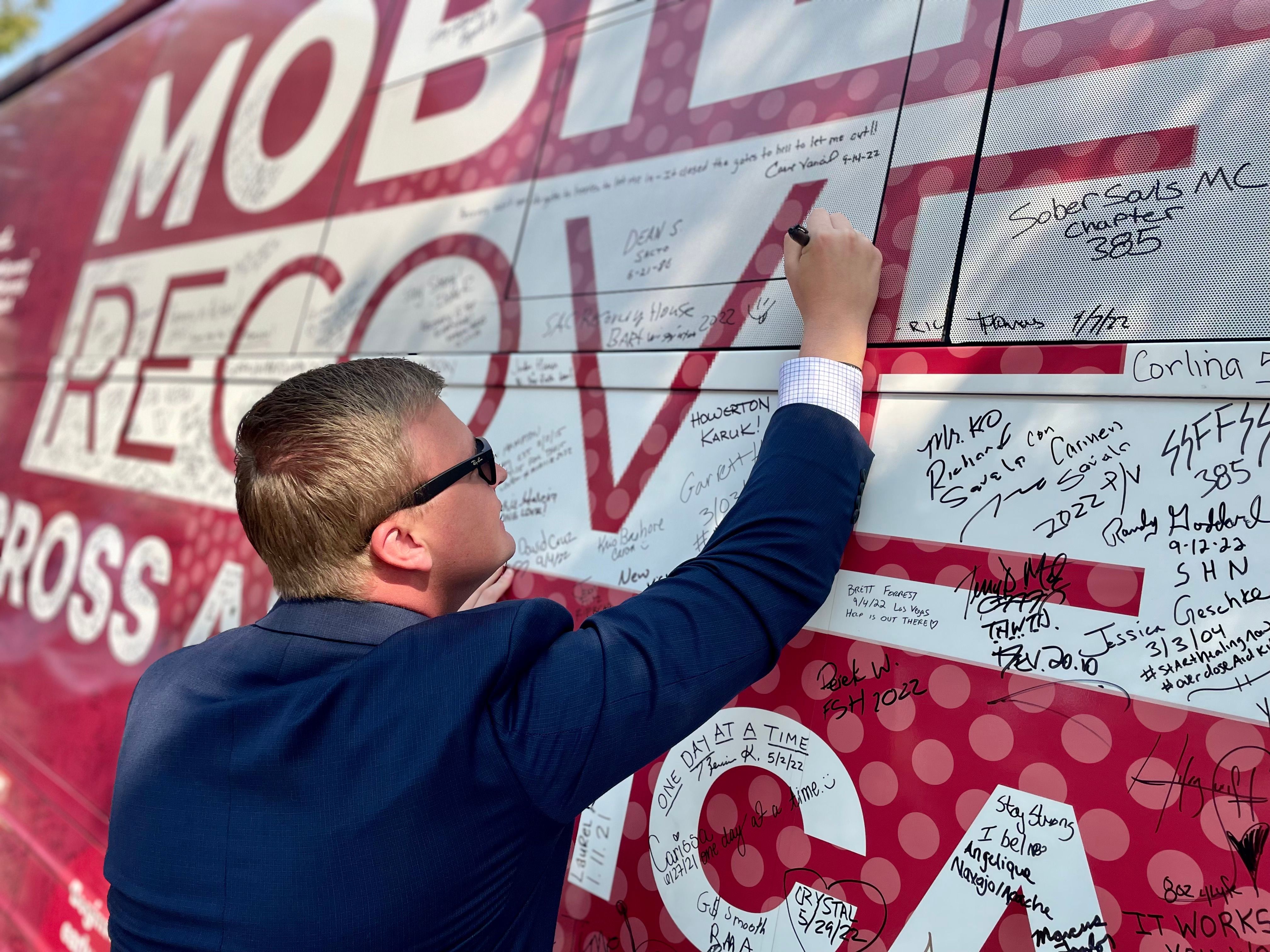

I wanted to provide space for people good at this job, that care about this job, that have lived experience, that they can make a livable wage without having to go and pursue some other discipline. And so I started going around the country. I started attending conferences, started getting asked to present and speak at conferences on this model and workforce development, leadership, peer support, sharing my story. It's allowed me to go to so many different places that were always on my bucket list of places to travel around the country, like California, DC, Vegas, and New York. My recovery and my journey through working in this space is what has opened up the doors and allowed me to go to all those places multiple times to do advocacy work, presentations and training. That's the progression. Early on it was just working directly with people, trying to help them get connected to resources. Then it went to working with the workforce and trying to develop a stronger workforce and investing in people providing those services.

EO: How does it feel going from boots on the ground, in-hospital peer recovery work, to helping implement an infrastructure? That's a huge evolution from being one of the first in the state to now overseeing a national infrastructure.

KB: How does it feel? Being in recovery, we help people. You give back. You serve others. There’s always that element of no matter what my job is, I'm always gonna have opportunities to help people directly.

And for a while, I maintained part-time employment at UAMS, still had calls that kept me involved with that part of the work. But it was a transition. I enjoyed it because I think I'm good at leadership administration and organization. I could offer different levels of this work as far as implementing programs, but there's that passion and meaning behind being boots on the ground working with individuals seeing them turn their life around and being part of that journey.

I have a really good network here in Arkansas, but I've built a similar one across the country where I know people and have been built and invested in relationships at all these different places that I've been able to travel and the organizations that they work for.

EO: Definitely. And I know you did work in the courts as well. Can you tell me about that experience?

KB: I took a job in the beginning of 2024 with the Supreme Court of Arkansas with the AOC – the administrative office of the court is within the Supreme Court. I worked in the legal department for specialty court programs. Drug courts, DWI courts, mental health courts, veterans treatment courts, et cetera. And so my job was doing advocacy work. From the state level, providing training and technical assistance to those courts and their staff, securing grant funding and administering those funds. It’s definitely different because the legal system is a different monster. I learned courts are even more difficult than hospitals to infiltrate, if you don't know somebody strongly on a drug court team or the judge, getting in there as a resource and being a bridge between that courtroom and the community. There's a little bit of a disconnect where there's resources, they're available, but they're just not a strong relationship between the community resources and the courts.

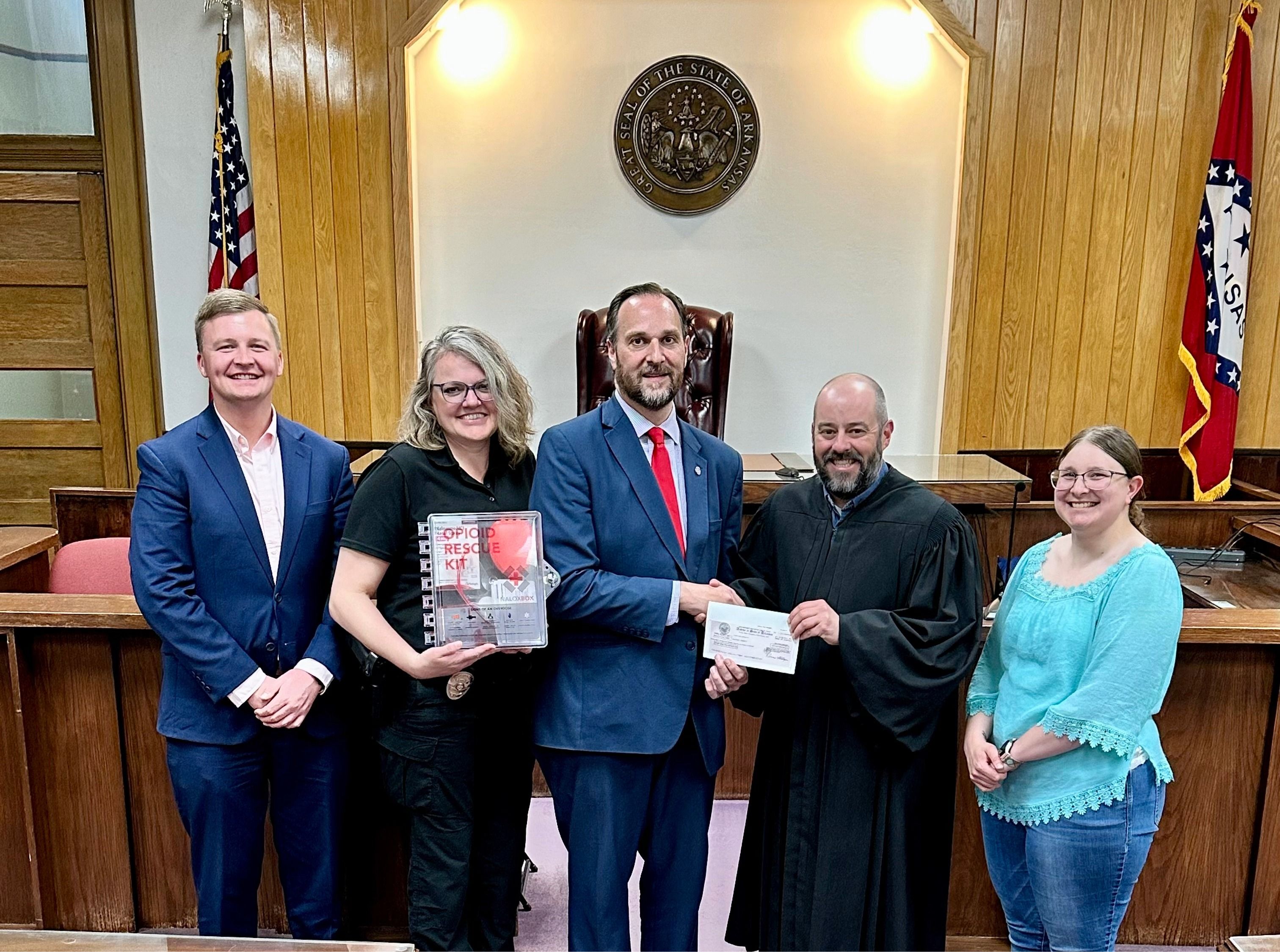

It's a highly political space. I worked for the Supreme Court and the director of the AOC is a mentor of mine. We secured a grant to install naloxone boxes in every single circuit in district court across the state. And with that we had thousands of cases of nasal spray Narcan. So we drove to literally every single district in circuit court in the state of Arkansas, dropping off and installing those boxes and dropping off the naloxone on those drives.

I enjoyed it. Every opportunity I've been given, I always enjoy it because I bring a unique perspective. I'm able to hold my own and have conversations with state agencies, judges, lawyers, and public defenders, someone in active addiction. I can be in those settings and have the conversation and communicate in the way that resonates with them.

When I was working for the courts, I did a lot of training. The first time I ever did it, I opened a presentation with four pictures of my mugshots. He was like, “This is the first time, maybe the only time you'll ever see an AOC employee do any kind of presentation where they're showing their mugshots.” It was a really cool opportunity to be able to improve the court systems and especially specialty court programs. I learned a lot about those programs myself.

I'd never gone through one myself, but they're very successful. Their success rates are very high. They are very difficult programs, very long, and lots of responsibilities for the participants. But their charges can be dropped and their records can be sealed, so there's high incentive to do so.

I'm going around to each courtroom and each drug court and being able to see the participants and talk to the drug court teams, [seeing] all these people doing amazing work and participants putting in effort to turn their life around.

EO: I wanted to ask about the landscape of addiction and overdose resources in Arkansas. From what you've told me it feels intricate and comprehensive. How can people in Arkansas best provide these resources? Whether that's naloxone, whether it's treatment, how, everyone can band together behind this singular mission of addressing the overdose crisis and addiction.

KB: There are a lot of great places doing great work. A lot of times it's siloed off. The recovery connections meeting I facilitate, one of the big pillars is collaboration. Acute behavioral health, detox, residential treatment, PHP, IOP, sober living, and the recovery community in general. All different parts in the continuum of care, but oftentimes aren't in close connection, relationship or communicating with one another when working with the same individual.

I think there's always room for improvement and we try to increase opportunities for networking and collaboration in this field. Both professionally and personally, the baseball game is a great idea, having a professional meeting is great, but also something fun, making memories and enjoying yourself providing spaces for more collaboration, it's not about competition. Plenty of people need help.There are unfortunately so many people that are suffering from substance use disorders that, it'd be great for us all to work ourselves out of a job one day, but as it is right now, there we don't need to look at one another as organizations or companies as competition.

We need to be collaborating in a patient-centered way that’s all about the client. What do they want? What's best for them and how can we work together? Individually you can be strong and have resources, but banded together, you're much stronger. You have many more resources, you can streamline the continuum of care, and make the experience so much better. So that'd be one thing I'd say is just collaboration. I think that something that y'all do really well is you're a kind like your marketing and media engaging with younger folks.

Naloxone, training, distribution. We can't get enough of that. We need easy access to naloxone, and it shouldn't be this thing where you have to worry about stigma going to the pharmacist or you have to worry about just even asking for it, even if it's not for yourself. If it's for a family member or a friend, just everybody should have it. It should be like Tylenol people's homes or in their vehicle. Everybody should keep it on you. Hopefully you never have to use it. But if you do, you could literally save someone's life.

EO: I would love to hear about your work with Landmark Recovery and how both your lived experience and career experience led into this role.

KB: Everything I described about my professional opportunities this job brings all those into one role. While I was working for the courts, my boss knew that unless some really great opportunity opened there, that it was a short term thing for me. We were all on the same page while I was there. I was reflecting on my previous jobs and asking myself, what did I really enjoy about them? What do I think that I was good at in those roles – my job title is a clinical liaison. But in the field, it's the business development person where your job is building relationships, maintaining relationships, networking, doing presentations, and then when someone needs help and needs to get into treatment, they call you.

Over the years, I have built all of these different relationships, whether it's from working at UAMS or helping other hospitals implement programs, to training and developing the peer support workforce on all of those roles, and then across the country and all these opportunities. I’ve built relationships along the way, and I think that I’m good at maintaining relationships and investing in them and prioritizing them.

Because again, it goes back to that original thing about how I think people are so unique and amazing and I just think that any opportunity to have a relationship with somebody, don't take it for granted.

Everything in my life could be pointed to two things. It could be pointed to my relationship with God and a relationship with somebody he's put in my life. Every opportunity has happened through those two things, you never know who you meet and what you may be able to do for them and vice versa.

All those relationships and that network learning to navigate systems of care, hospitals, treatment facilities, learning how to do that, has prepared me for this. I came into this role with all these relationships already in place.

I'm very familiar with how to navigate treatment. How to navigate recovery resources, how to navigate the legal system because of my previous jobs. I've done hundreds of presentations and public speaking engagements, so marketing and talking in front of people is the thing that I feel comfortable and natural with doing.

This job has really taken all of those pieces and that's what I really loved. I'm not a go to the office every day kind of person. I like to be in the community connecting with people. I like to support and help people. My goal at the end of the day is, how can I use all the relationships I've formed over the years to make it as easy as possible for somebody to access treatment and recovery resources? When they ask for help, past the barrier of shame, embarrassment, judgment, hopelessness, and stigma.

In my opinion, it should be the easiest thing to do. But unfortunately, it's across the board that getting into treatment can be very difficult. You can get met with obstacles, resistance and challenges. I don't have transportation or we only do admissions eight to five Monday through Friday.

One of the things I love about Landmark Recovery is our system is designed to move towards the individual. We don't expect you to have everything together and to be operating at a hundred percent to move towards us. We move towards them. It's a very easy, simple process. If you call, we do a screening over the phone, which is about 10 or 15 minutes, and if you're ready, our transportation team is on the way to your address. Depending on how far you live, we provide transportation from all across the state and surrounding states. So depending on how far you live, that really determines how long it's gonna take for us to get there. Because when you're ready, that window of willingness, motivation and opportunity can close fast. If it's Sunday at nine o'clock at night and you want treatment, we can make it happen. We'll have you in treatment tonight at the facility. That's been my favorite job thus far. I definitely loved all the other opportunities but this one, combines all the things I loved about the other jobs into one. I still support the state DHS with the peer program, providing insight, consultation and support. We're in the middle of evaluating the peer support program and seeing what changes might need to be made. I'm on the National Steering Committee for the Center of Addiction Recovery Support and represent region six. It used to be called the Peer Recovery Center of Excellence, it’s now called the Center of Addiction Recovery Support. I still do some consulting with implementing peers and hospitals and supervision models. But as far as my day job, this role has been my favorite that I've had thus far.

EO: Amazing. I've heard you talk about making treatment as accessible and as easy as possible for someone who has that window of willingness. You've also talked about the need for collaboration between entities in treatment and recovery. Are there any other paths you envision for the future of peer support and treatment in Arkansas?

KB: Having peer support specialists in treatment centers in Arkansas is an important thing.There's a couple that have people that have gone through the training on staff, but they're in a different role because in Arkansas there's not a billing mechanism for peer support services. So they're not actually a peer support specialist when it comes to their role within the facility.

But I think that having peers and people with lived experience that have this training and certification into the clinical setting is very important. I don't know what will actually happen until we find a way to start billing insurance for their services.

At the end of the day, that's what it comes down to a lot of times, is the bottom line and being able to generate revenue. So I think that sustainability is something that I'm always focused on when it comes to the peer program in Arkansas. How do we sustain this program without grant funding?

How do we get to a place where this position generates revenue? For the most part, it's a cost savings for the hospital when I'd make cases and present to hospitals about implementing this type of program. I'll talk about cost savings. If we can keep this individual that comes to your emergency department every two weeks from returning for six months, how much money did that save the hospital? And if that person gets into recovery and never comes back, they start seeing a primary care provider. They start getting their regular check. There's no need for them to come to the emergency department outside of a legitimate emergency.

They're not showing up every couple weeks, you're saving the hospital a lot of money. When it comes down to it, you're saving your staff's time and a lot of attention. You're also saving taxpayers money, because taxpayers are funding some of the hospital's programs and research. I think funding sustainability and the research and data components tell the story. It's great to tell the narrative, but in a lot of ways, in a lot of places it doesn't mean anything. You can't back it up with numbers, and show the real impact. Research is an important element to the work we do that maybe there’s not as much of here in Arkansas.

EO: Is there anything else you want to add?

Kyle: If I can ever help, If I can provide any type of support or resources, do not hesitate to call. How can I make it when you call, whether it's you, with your family, or a social worker, how do I make that process easier and more efficient for you past the part of being willing to ask for help? Let me clear the path using my relationships to make it as easy as possible because. They're the only person that can walk the road. They’re the only person that can put the work in that's required, but I know that there are certain things that I can do to remove obstacles and barriers that can make it a little bit easier for them. If I can help, please reach out.

REACH KYLE DIRECTLY

(C) 501-794-9930

(E) Kyle.brewer@landmarkrecovery.com

VISIT LANDMARK RECOVERY HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION